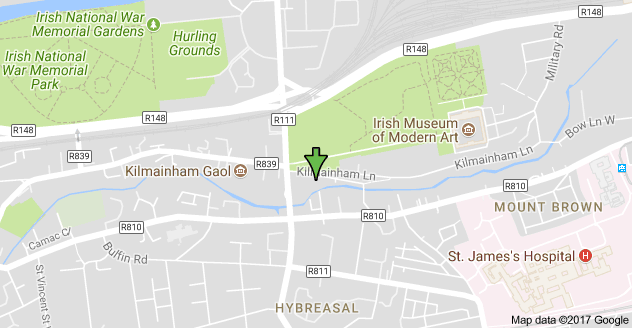

The River Camac (sometimes spelled Cammock, or, historically, Cammoge or Cammoke; Irish: An Chamóg or Abhainn na Camóige) is one of the larger rivers in Dublin and was one of four tributaries of the Liffey critical to the early development of the city.

The Camac forms from a flow from Mount Seskin southeast of Saggart, to the southwest of Dublin city, and other mountain streams as well as an 18th-century diversion from the Brittas River tributary of the River Liffey. It flows through a mountain valley, the Slade of Saggart, southwest of the broad Tallaght area and east of Newcastle, then past Saggart, through Corkagh Park and then Clondalkin, near which it is sometimes called Clondalkin River. The Camac then continues on to Inchicore where it is tunnelled under the Grand Canal before a bridge crossing at Golden Bridge. The Camac runs behind Richmond Park, home to St Patrick’s Athletic and gives its name to the ground’s ‘Camac Terrace’, and Kilmainham, where it runs behind the jail museum, before entering the Liffey alongside Heuston Station, a little upstream of Sean Heuston Bridge. The river was tunnelled underneath the railway station when it was built in 1846.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/River_Camac

Little remains of the farms and industry that developed along its banks, and modern developments seems to regard it as a hinderance and not a benefit to the area. One industrial building remaining is Kilmainham Mills. According to the Kilmainham and Inchicore Heritage Group, it was in continuous use from the sixteenth century until 2000.

Little remains of the farms and industry that developed along its banks, and modern developments seems to regard it as a hinderance and not a benefit to the area. One industrial building remaining is Kilmainham Mills. According to the Kilmainham and Inchicore Heritage Group, it was in continuous use from the sixteenth century until 2000.

Architectural Merits: http://www.buildingsofireland.ie/niah/search.jsp?type=record&county=DU®no=50080060 –

The DSC Constituency Group discussed how might the Mills be saved as a local example of our industrial history and operate as a community owned tourist attraction. The following information is taken from an article in The Dublin Inquirer and has been edited by myself for brevity. I’m relying on the accuracy of the original article to give the recent past. In July 2017 the site is derelict.

In 2002, Dublin City Council drew up a conservation plan for the site. It “recommended that the archaeology of the site be disturbed as little as possible and laid particular emphasis on the historical development of the Mill Race when it was internal to the Mill building,” said an Irish Times report in November 2003. The conservation plan listed structures within the mill in order of historical importance, and was prompted by Damian Shine’s efforts at the time to redevelop the site.

In 2003, then-owner Damien Shine’s company Charona Ltd owned the site and was in line to redevelop it, with plans for 48 new residential apartments. In February 2005, Shine was granted planning permission for the 48-apartment development. Nothing happened.

The debts incurred from the failed 2003 redevelopment eventually came under the remit of the National Asset Management Agency (NAMA). Charona Ltd was liquidated, and the mills was listed on a 2011 spreadsheet of NAMA-enforced properties, circulated on thestory.ie.

The debts incurred from the failed 2003 redevelopment eventually came under the remit of the National Asset Management Agency (NAMA). Charona Ltd was liquidated, and the mills was listed on a 2011 spreadsheet of NAMA-enforced properties, circulated on thestory.ie.

According to the article, Dublin City Council and a company named Kilmainham Mills Ltd tried to revive the mill and reopen it as a possible heritage centre. Anything to do with NAMA seems messy as NAMA are mandated to get the best possible price. A further problem seemed to be that Shine lived within the grounds of the mills and maybe refused to sell or vacate the site. Whether NAMA sold the site and to whom is unclear, as there seems to be no public information.

Maurice Coen, a Kilmainham resident, established Kilmainham Mills Ltd in 2013. The company was set up at the behest of Dublin City Council, according to Coen. “The plan was that [the council] would go forward, purchase the mill and it would be handed over to our group,” he says. “We would then have a 10- to 15-year company contract to build it into a visitor centre.” When Kilmainham Mills Ltd was established, there were numerous EU conservation and heritage grants available. The idea was to fund the centre with money from some of those, he says.

“The mill’s st ill pretty sound, but the roof is coming in in many, many areas,” says Coen. “My argument was that with every rainfall, every storm, more damage is being caused. The price of reconstructing would be dramatically increased.”

ill pretty sound, but the roof is coming in in many, many areas,” says Coen. “My argument was that with every rainfall, every storm, more damage is being caused. The price of reconstructing would be dramatically increased.”

Today, it’s overgrown with ivy and weather-worn and vacant. “It was really stuck in the mud, but now it’s really stuck deeper than it ever was,” says heritage group secretary Michael O’ Flanagan. “It’s continuously deteriorating.”

A local group ‘Save Kilmainham Mill Campaign‘ with a Facebook Page meets monthly in the Patriot Inn.

Another fine example of our historical heritage within the constituency, the Iveagh Market, was discussed by the group. The developer, Mr Keane, won a tender to regenerate the market in 1996 and was given a 500-year lease on the building. In 2007 he received a 5 year planning permission to renovate this beautiful building, and Mother Redcaps next door, and add a hotel. The permission was extended by 5 years which expires in August 2017, but has been done nothing and during this 20-year period the building has continued to deteriorate. Sad, very sad! As the tennant has neglected maintenance for 20 years, we call on Dublin City Council to now repossess this building and restore it, and the neighbourhood, to its former glory.